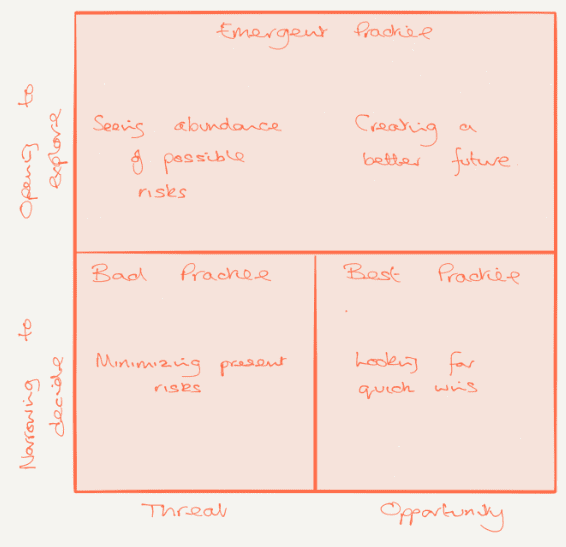

A couple of weeks ago, Edutopia published an article entitled 5 Fun Gym Games to Get Kids Moving. I found the subsequent commentary on the article, mainly via Twitter, absolutely fascinating. Whilst I could understand many of the points made from a range of perspectives, the conversations around the article made me consider how I’ve changed my thinking about practice. There is a seductive certainty in establishing both bad and best practice within PE, putting us on the search for silver bullets or a one size fits all approach, however things are rarely that simple. As Jean Boulton and colleagues in Embracing Complexity put it “working on the basis that certainty exists and prediction is possible is probably more dangerous than erring on the side of uncertainty and tentativeness.” This has led to a change in my mindset (to a ‘it depends’ mindset), questioning whether the labelling of practice as only either bad or best is the way forward?

‘Bad Practice’ (minimising risk)

Some of the commentators considered the piece to promote ‘bad practice’ within PE and called for Edutopia to take the article down. In a time where there are competing constraints on the curriculum, giving breathing space to articles that potentially paint the PE profession in a bad light are not helpful for the advocacy of our subject. Looking at my own teaching bad practice occurs, as does failure. I don’t deliberately plan for it. When it does happen, we often we look to hide it or sweep it away, but when we do we also give up the potential for some rich learning. It would be better to shine a light on it and stick it under the microscope.

Atul Gwande in the Checklist Manifesto and Matthew Syed in Black Box Thinking explore the differences between the medical profession and the aviation industry when it comes to bad practice. Both make that point it is that aviation industry that has made the biggest leap forward on safety, by not shying away from it’s mistakes, but trying to learn as much as possible. The online space the #physed community has created for professional development has made a big impact on my practice. However we are at risk of turning it into an echo-chamber, where only the agreed best is shared. By labelling practices as ‘bad’ we create a stigma, which prevents people sharing. If we can create a culture where teachers are honest about their practice, we can then try debate it rationally and out in the open. Then the entire community can learn from this debate. A recent exchange on leadership research provides a good example of how we could go about that. That is the way we develop and how we can be viewed as professionals. Obviously promoting bad practice as good can have a negative impact on PE, but I think closing down any potential debate by removing what may be considered bad practice is ultimately worse.

‘Best Practice’ (quick wins)

We are always in search of ‘best’ practice. My quest has lead me to Game Sense, Cooperative Learning, Sport Education and Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility. Yet just because PE Department A has success implementing Cooperative learning structures it doesn’t mean that PE Department B can use the same process and expect the same outcome. There is always room for new thinking and innovation, or at least there should be. By awarding the title of ‘best’ to practice we stop questioning it. We make the assumption that by implementing those practices our job is done. It encourages a ‘copy and paste’ approach, without us really thinking of the consequences and opportunities of adopting them.

Adoption is difficult to do because two contexts will never be exactly the same. Is this really the best we can do in a subject where nothing is certain or exactly repeatable? Philip Tetlock in Superforcasting argues that “Beliefs are hypothesis to be tested and altered, not treasures to be protected.” The same could be said for best practice in PE. Perhaps the first step to doing that is by dropping the label ‘best’. When we hear something is a best practice in PE do we consider who has said this and why do they get to determine why it is best? Do we try to understand who it is best for and in what context it might be best? The online #physed space can create a herd mentality, uncritically and evangelically embracing best practice, with no one exercising their professional judgement and decision making. If we don’t drop the label of best practice, will we eventually become dogmatic in our approaches, entrenched in our views of what is best, making our practice unquestionable and unchallengeable. The thought of walking down that path makes me uncomfortable.

Emergent Practice?

Looking at our practice only through the simple lens of ‘bad’ and ‘best’ is narrowing. Perhaps this wouldn’t be a problem in PE, if teaching and learning was a simple INPUT = OUTPUT, but it isn’t. This mindset shuts down the debate surrounding the practices in our classroom and we can all benefit on improving on the errors committed by ourselves and others. I’m drawn to the idea of emergent practice, but it seems emergent practice needs considerable practice. Rather than just focusing on minimising risks or looking for quick wins in our practice we should be in search of something both more durable and flexible. To get there we need to get our practice out in the open. It is much easier to learn and get better without the threat of ‘bad’ and ‘best’ practice looming over our heads.

By having a different mindset of practice we start by asking different questions about what we do. To ask for more than a shallow justification of what is happening, but for what purpose and where does this sit in the bigger picture of that purpose. This changes our mindset and the questions we ask about our practice. Jennifer Berger and Keith Johnston in Simple Habits for Complex times make the point “Asking different questions is about shifting the mindset, and it is a reciprocal move: your questions can shift your mindset and your mindset can shift your questions.” Perhaps the biggest barrier to improving our practice in PE is simply to remember to ask different questions, but can we do that when we label everything as either bad or best?