In the last few week I’ve had numerous conversations about school sport. Due to Covid-19 it has been missing and schools want it back. But why? Whether it was a Headteacher of small primary school in rural Somerset, a Head of PE in a large inner city comprehensive, a Director of Sport in an all boys grammar school, external sports coaches in an independent school or student teachers on their PGCE there tends to be a common response.

The response is that school sport is to help children to become disciplined (because they lack character), learn how to excel at competing and to help with them deal with the consequences from winning and losing (because life is just one big competition). There are uncritical assumptions hidden in these justifications. Firstly, that just by playing sport your behaviour will automatically become more virtuous and secondly, that life is a competition. As my good colleague Greg Dryer always quips, life has demanded far more collaboration from him than actual competition.

These justifications for school sport provide an explanation why the dominant provision has very clear boundaries. It is an achievement model, requiring formal participation, where the fundamental principle that gives action meaning is competition and ranking against others.

The focus then becomes about which sports the school should offer (so they can compete in) rather than asking what type of school sport provision might be the best for their children. Winning leads to trophies, kudos and publicity. School’s take pride in ‘producing’ county, regional or national players and champions. Does this version of school sport support the needs of the children, or are the children supporting the needs of the school through sport?

However there are alternatives to the formal school sport model, to the achievement school sport model and to the competitive and ranking school sport model.

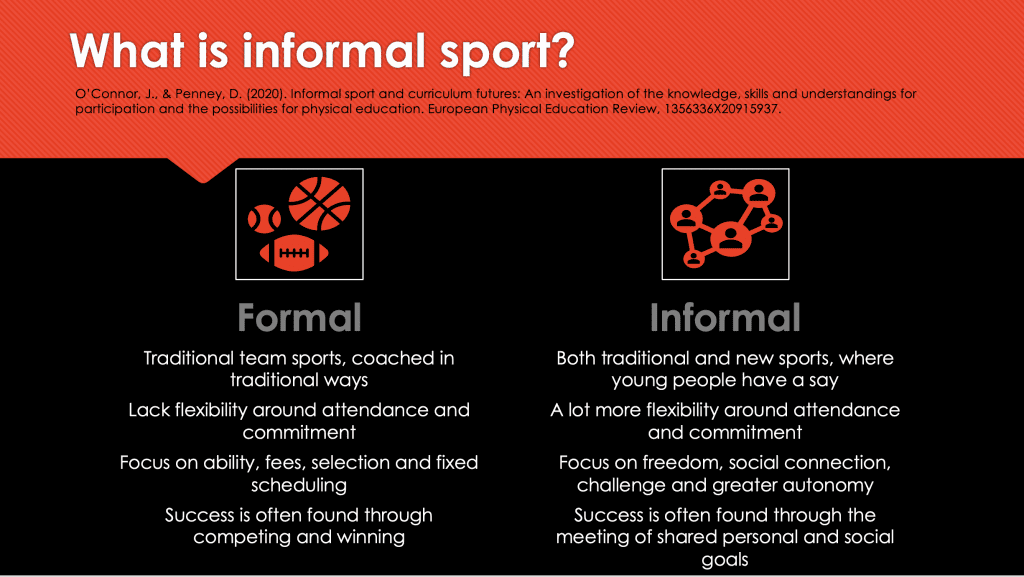

O’Connor and Penney (2020) make the case that there is a growing interest in ‘informal sport‘ which is characterised as participation not linked to formal clubs, traditional competition or representative sport structures, an example of which is Park Run. They recognise that traditional forms of structured sport remain significant for many children and I agree. However they also point out it has been the dominant form and ask the question that as young people get increasing autonomy whether or not participation within formal structures appeals to them as they now have many competing demands in their lives.

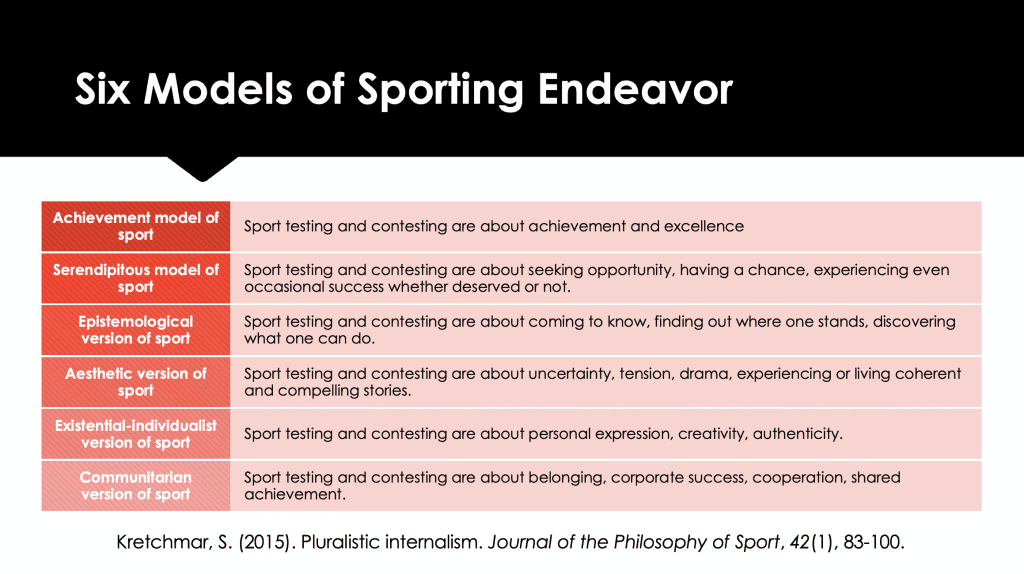

Kretchmar (2015) offers alternative models of sporting endeavour. In over 20 years of working in school sport the achievement model is by far the most common. This model takes its primary values from the world of work – solving problems that offer preparation, progress and the development of the virtues of effort, dedication and skill.

These maybe worthy aims, but in my opinion, they are also the aims of adults for children. They also continue to narrow the educative role schools play in a child’s life simply to qualification and a preparation for work. Do we need school sport to also do that as well? Especially as it can provide, in Kretchmar’s opinion, a host of possibilities. Further he states that the serendipitous model of sport is more developmentally appropriate for young people. This model takes its primary values from the worlds of play and spirituality and seeks temporary relief from obligations and the meritocracy of work, by providing ‘delightfully interesting problems‘.

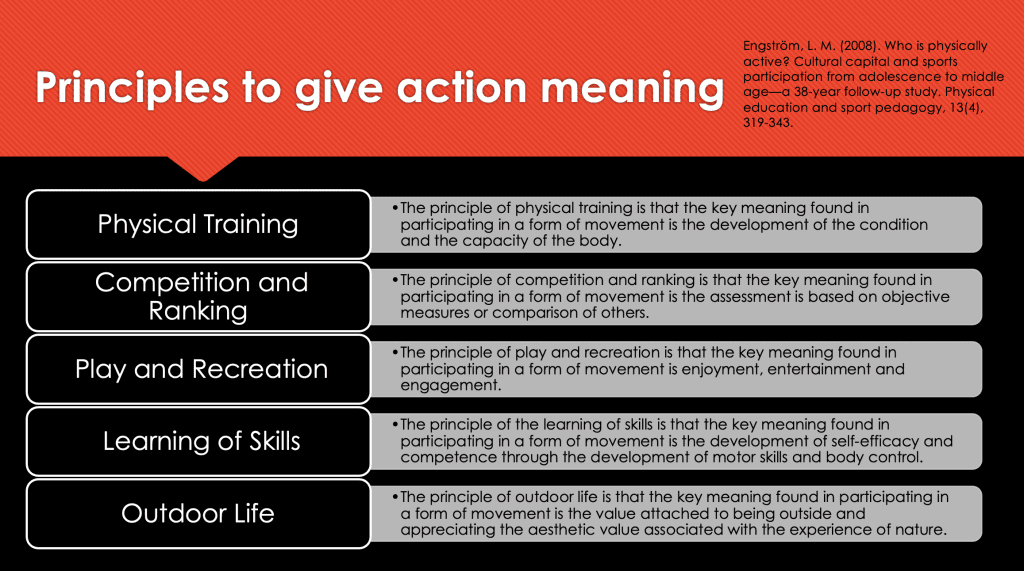

Engström (2008) adopts a Bourdieusian perspective which highlights different principles or logic within the field of sport that give an action meaning. Every sporting activity can be described on the basis of these meanings – his example of skiing demonstrates a sport that can offer the full range of meanings if intentionally designed for. His research leads him to conclude that learning opportunities in school sport must be both broadened and deepened beyond competition and ranking as – “this is particularly important when it comes to basic knowledge and skills that constitute essential prerequisites for an active participation in different kinds of exercise and outdoor activities.“

Boundaries can be unhelpful. Especially when trying to create something that is transformational, inclusive, meaningful and educative in children’s lives. What these authors offer is a blurring of the dominant lines, as what really matters for school sport is what fits with the lives of the young people we teach. Weakening theses boundary lines shifts how school sport gets classified. This means we can open up possibilities for something new that can include a wider range of young people and provide greater personal meaning in their lives.

To see school sport solely through the narrow lens of achievement, and competition itself through a myopic focus of winning and losing, is to miss out on the richness of experience that school sport could provide. Kretchmar, Engström, O’Connor and Penney all offer alternative models of school sport that if we consider begin to blur the boundary we have collectively put up around it.

In an interview with CNN John Amaechi proclaimed “Sport is an empty vessel“. What we fill it with is important but the boundaries we have influence that. When we start thinking about what educative and meaningful experiences we want young people to have in school sport, I’m unsure if we will always come up with a model is formal, strives for excellence and uses competition to compare and contrast. Especially if we bring those young people into that process of not just filling it, but shaping the boundaries that surround it.