“Skills are not practiced diligently; old habits are never relinquished; new habits are not developed; attitudes are not changed; nobody is inducted into any one of the many movement subcultures that are asking for new members; learning plateaus are never encountered because they are never reached; and advanced challenges are never met. Much of the good stuff of movement remains hidden. The reason for this is not hard to find. These achievements take commitment, time, effort, and persistence.” Kretchmar, 2006

An often espoused intention of a secondary school PE curriculum is to help young people find an activity they like and will continue beyond PE.

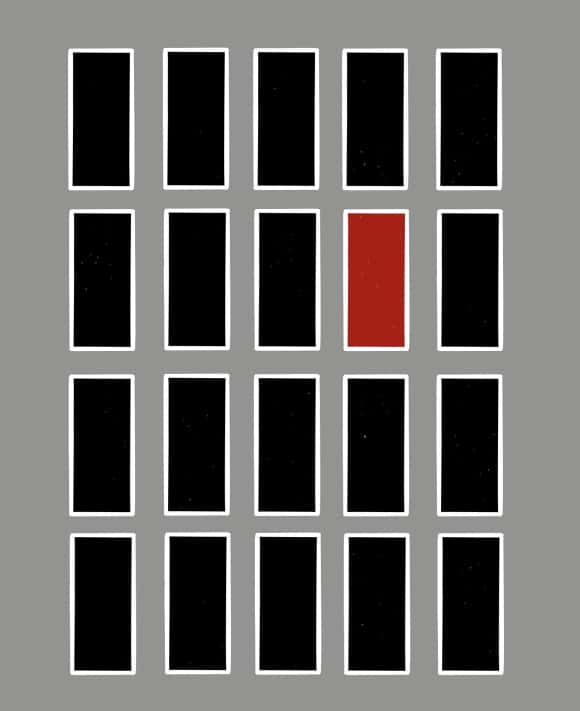

In order to achieve that intention it makes sense to provide a variety of activities for young people to experience. The result of this assumption is to produce a programme which Sidentop (1977) labels as a ‘multi-activity‘ approach to PE. Curriculum decision making and design is then around which activities (usually traditional team sports) are covered, often in blocks of work, which fit neatly into half terms. If a school has two lessons of core PE a week, they may be assigned to a different activity, ensuring a child can experience up to 12 different sports over the course of the year.

The focus of learning of these short blocks of activity are often ‘sports techniques‘ (Kirk, 2009). Sport techniques are specific movement patterns or solutions that have been identified to produce a clearly identified goal within a sporting context, then disassembled into various parts and learnt through isolated mass practice. This can lead to an environment where high grades, personal achievement and praise is obtained by those individuals who can accurately replicate technique which is rather different from the original intention of finding activities one might enjoy beyond PE.

These short blocks, with an overt focus on reproducing accurate decontextualised technique have little chance, if any, of producing significant personal meaning or skill. Alexander (2013) says this approach keeps ‘three dirty little secrets‘ from those outside the profession – i) they don’t develop motor skills ii) they don’t develop game performance and iii) they don’t develop health and fitness.

The short period of time might also be detrimental as the experience of frustration that comes with early attempts at development may result in avoidance behaviours with activities and PE in the future (Sidentop, 1977). Even if taught well, this ‘multi-activity sport technique’ focused curriculum has serious limitations, with perhaps its most serious weakness that of a lack of authenticity in terms of how sport is represented beyond PE (Kirk, 2004).

Success within this programme is down to an individuals previous and ongoing movement experiences outside of PE. A movement version of the Matthew Effect, where the movement rich get richer and the movement poor remain impoverished. Ennis (1999) goes as far as saying that no curriculum design in PE has been as effective in ‘constraining opportunities and alienating girls‘ as that of a coeducational, multi activity programme which focuses on sport techniques.

Locke (1992) would describe this curriculum approach to PE as ‘a programmatic lemon‘. Using it to make lemonade may be beyond even the most skilful PE teacher – instead it contributes to young people’s disaffection to physical activity and sport, poor motor learning and furthers the marginalisation of PE as an educational subject.

A brief check of the rules, more time talking about the techniques than actually practising them and with very little play in developmentally appropriately games – we are mistaken if we think a child will find their sporting muse through this brief introductory curricula (Kretchmar, 2006). Providing multiple activities over short periods of time in the hope that a child becomes physically educated is akin to regularly taking a child to an all you can eat buffet in the hope that they will learn how to cook nutritious meals. Even the original PE curriculum intention of helping a young person to find an activity they like might be misplaced, as there is as much chance of them learning that there is nothing they like as there is something they like. An indefinite testing, tasting, sampling and searching for one’s perfect mate is counterproductive (Kretchmar, 2006).

Teaching for learning and for meaning requires time and patience – we can’t talk about “teaching PE without any evidence of an intention to produce learning” (Ennis, 2014; Crumb, 2017). If we want to keep young people ‘busy, happy and good’ (Placek, 1983) or provide them experiences of pleasure (Gerdin and Pringle, 2017) then technically focused, short duration sports units may suffice. If however, we see sport as a culturally relevant form of movement that is to have an educational place within the secondary school PE curriculum, then we need to provide extended opportunities that support both competency and meaning making. That starts by asking difficult questions about ‘multi-activity sport technique’ curriculum design. It may mean giving up some, but not all, breadth for depth. For without depth we will keep children and sports at arms length (Sidentop, 1977) and it is unlikely they will form enduring, positive and potentially meaningful relationships with each other.

Further Reading:

Alexander, K. R. (2013). Some seed fell on stony ground: Three models – three strikes!. In Proceedings of the 28th ACHPER International Conference, Melbourne 2013 (pp. 1-8). Hindmarsh, Australia: Australian Council for Health and Physical Education.

Crum, B. (2017). How to win the battle for survival as a school subject? Reflections on justification, objectives, methods and organization of PE in schools of the 21st century. RETOS-Neuvas Tendencias en Educacion Fisica, Deporte y Recreacion, (31), 238-244.

Ennis, C.D. (1999). Creating a culturally relevant curriculum for disengaged girls. Sport, Education, and Society, 4, 31-49.

Ennis, C. D. (2014). What goes around comes around… or does it? Disrupting the cycle of traditional, sport-based physical education. Kinesiology Review, 3(1), 63-70.

Gerdin, G., & Pringle, R. (2017). The politics of pleasure: An ethnographic examination exploring the dominance of the multi-activity sport-based physical education model. Sport, Education and Society, 22(2), 194-213.

Kirk, D. (2004). Framing quality physical education: the elite sport model or Sport Education?. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 9(2), 185-195.

Kirk, D. (2009). Physical education futures. Routledge.

Kretchmar, R. S. (2006). Life on easy street: The persistent need for embodied hopes and down-to-earth games. Quest, 58(3), 344-354.

Locke, L. F. (1992). Changing secondary school physical education. Quest, 44(3), 361-372.

Placek, J. (1983). Conceptions of success in teaching: Busy, happy and good? In T. Templin & J. Olson (Eds.), Teaching in physical education (pp. 46–56). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Siedentop, D. (1977). Physical education: Introductory analysis (2nd ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown.