Most people will at some point adopt a movement or fitness practice with the intention of improving their lives and rectifying the relationship with their bodies. If the statistics on obesity and chronic pain are any indicator, most of these people are failing to adhere to even a basic protocol. With so many modalities and trends claiming the superior position, the sheer variety in choice can be crippling. In the face of a global ‘bodymind’ crisis, the important thing is to encourage others to begin exploring and to hopefully adopt any practice at all. In this piece we will examine how psychological and archetypal predispositions might effect one’s view of movement and practice, and how we might better understand ourselves and choose a path appropriate to our own individual nature. Many people feel alienated from movement and might be looking in places ill suited to their personalities. I would like to suggest taking an honest and critical look at our own psychology, and to begin assessing if we are properly aligned with environments that will help us thrive and reach our goals.

The worst idea in all of pop psychology is that the mind is a blank slate at birth. Moral and experiential predispositions are in large part biological. Each of us has a certain place we occupy on the spectrum of order and chaos. In many ways this is assigned, and we must learn to work within the bounds of our natural inclinations. Of course, built-in does not mean unmalleable; it means organized in advance of experience. These innate tendencies are reflected in how we choose to vote and which activities we choose to pursue. We will examine two sets of philosophical frameworks that evolved completely separately from one another in a hope to prove that these structures are universal, bottom up, and not unique to a particular cultural paradigm.

Apollo is the god of light, interpreted as the ruler of the of the self-concious, of the abstract and conceptual. Apollo represents individuation and structure, the masculine aesthetic of the Western eye. Many of us are instinctively familiar with the kouros, the athlete, the beautiful boy. The Apollonian ideal strikes a proud figure against the chaos of nature, organized and collected, proportioned and perfect. We are surrounded by this ideal continually as we in the West live in a society that has become an expert at honing and expressing these qualities. Science and mathematics have served a remarkable role in our development as a species. We can fly higher, run faster, and live longer because of abstract and conceptual thought processes. Conservative and organized. Efficient and streamlined. Through abstraction we have been able to better ‘control’ nature and produce predictable results in sports performance and rehabilitation. Apollo is represented by our fascination with organization and improvement, the desire to build an island of supreme aesthetic and symmetrical beauty. Though responsible for many positive turns throughout human history, the over-expression of the Apollonian ideal can lead to a separation from feeling, self, and nature.

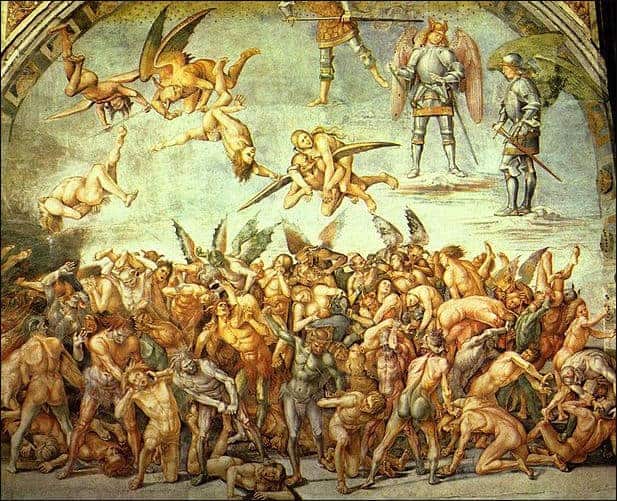

Dionysus on the other hand is the god of chaos, emotion and instinct. In opposition to straight lines and aesthetic borders, the Dionysian mind is the state of supreme collective absorption. Not just festival and revelry in the contemporary sense, but a full immersion into the disorder and miasmic turbulence of nature. The messy realities of birth and death, disease, and emotion. The manic peak and the lowest valley. The gentle caress of adoration and the violent loss of control in jealousy or rage. In many ways humanity is literally born of Dionysus. All of nature participates in a beautiful, apathetic dance of creation and destruction. The Dionysian framework provides an interesting explanation for the nutritive phenomenon of selflessness in regards to deep concentration or collective absorption. The desire to be liberated from the temporal anxieties of self and re-unified with the whole of nature becomes apparent every time a society would attempt too much order in the Apollonian sense. Revolutionaries who desire to throw off the yoke of oppression and tradition provide an important balancing force, but order must return after the dust settles or things would deteriorate beyond repair.

These two ideals rarely exist in extremes, as the full expression of either predisposition would be highly undesirable. Unchecked hedonism, in the end, becomes just as oppressive as an excess of rational purity. The artist stands on the knife edge between order and chaos. Using Apollonian techniques of abstraction and separation, they serve as a medium between the unknown and the known. This is a dangerous pursuit, as many who explore the boundaries do not return. But those who do return and have the skill to communicate what they’ve seen provide society with vital catalysts for growth and introspection. A very small number of these successful artists are thrust into the spotlight, showered with praise, and possess a very unique place in society. What people do not see however, is the immense graveyard of those who have danced with madness and did not return from its trance. Art is of value precisely because it is dangerous.

While the Gods of ancient Greece were weaving stories on mount Olympus, equally poignant philosophies were fermenting in Asia. For more than 2000 years, China maintained the same system of government and is responsible for an incredible percentage of important innovations in technology and infrastructure. Though the China we know today has been eviscerated by colonialism and Maoism, the influence of Imperial Chinese culture is still expressed throughout all of East Asia. The question of why the Enlightenment happened in Europe and not China remains one of the most fascinating intellectual adventures, capable of filling volumes and occupying scholars for generations. How different would the world be if the scientific method was perfected in Imperial China? Analogous to the Greek dichotomy of Apollo and Dionysus, Confucianism and Taoism have played side by side in east Asia for thousands of years. Many people will be familiar with Taoism on some level, but tend to be relatively blind to Confucianism, which holds equal cultural influence. It is when Taoism is juxtaposed with Confucianism that we can begin to realize that an entirely different culture came to similar truths about the spectrum of human behavior.

Confucius was a politician, musician, and philosopher. His teachings are best understood as an attempt to preserve filial piety and social order through education and ritual. Bearing similarities to the Apollonian ideal, Confucianism posits that we must become ‘more human’ through hard work, education, and endless repetition. The sacrifice of the body and mind to practice and discipline can certainly yield powerful results, but can also leave one feeling machine-like and devoid of meaning. Confucianism represents itself today with the cliche image of a Japanese business man slumbering on the train in exhaustion, or the diligent college student neglecting their basic needs in favor of lucubratory study sessions. In the West we also have phrases like ‘no pain, no gain’ and ‘I’ll sleep when I’m dead,’ that reflect a vigorous Confucian dedication to efficiency and productivity.

Taoism on the whole is in some ways the inverse of Confucianism. To dramatically summarize, Taoists seek to ‘do nothing’ and to ‘unlearn,’ as the way of nature is already perfect and contained within. To the Taoists, rigid structure and the amassing of knowledge is a forced way of being and can never lead to human flourishing. One who practices the way seeks a state of flow and intuition uninterrupted by conceptual thought. Eschewing objective outcomes in favor of harmony with nature, we can find the Tao in open ended and creative activities. The refinement and propagation of Taoist practices have served as a balancing force for hard edged Confucian ideals over time, and may help explain why for all of its advancement, science did not originate in China. In an ironic turn of events, modern science is trending to support Taoist intuitions of harmony with nature and a more relaxed pace of living.

So how does all of this tie into movement and fitness practices? I believe it is safe to say that each of us falls on some point of the continuum described above. What is right for us is not imposed externally, but rather built internally upon reflection of our own unique psychology. One who falls more heavily on the side of order may find it sustainable to adhere to structure and repetition, while one who is a friend to chaos might have better luck with open ended, ooey-gooey modalities. Fads come and go and popular culture changes. Yes, we can quibble at the highest levels of efficacy over which protocol produces the ‘best’ results, but in a climate where the majority of the population suffers from a basic movement deficiency, this is insular and masturbatory. The prime focus should be on reaching those who have not yet developed a practice or are struggling to find the right fit. In a culture that promotes movement less and less, we should find ways to deconstruct barriers to entry and ensure that people feel empowered to explore and adopt a modality that is the correct fit for their individual needs.