When Clayton Ray, a baseball pitcher at Cabrillo College, walked into Apiros, he was worried his baseball career was done before it even got off the ground. He had been sidelined by elbow pain for eight months, and couldn’t throw despite having done the standard physical therapy.

He had already progressed through physical therapy’s greatest hits: he stretched, he iced and heated up his arm, he got massaged, he sustained minor, cute little electric shocks that convulsed his muscles, and despite being a strong collegiate athlete, he worked out his arm muscles with small stretchy bands that could only challenge toddlers. Once he completed six months of this program, he returned to pitching—his elbow hurt immediately. Of course it did. Nothing he did over that time improved his mechanics, muscles, or his connective tissue. His rehab was more like spa treatment. He then planned to take a year off and see what happened. That’s when we, luckily, met.

Most athletes find Apiros. I found Clayton. I was at one of Mitch Haniger’s batting practices when I got to talking with the gym owner, Joey Wolfe. At the time, I was looking for a pitcher with chronic elbow pain who had already tried standard rehab. I wanted a case study. I thought I knew what the standard elbow treatments missed and why elbow pain is such a pervasive issue. So I asked Joey if there was anyone in his facility who fit the stereotype and that’s when he introduced me to Clayton, a 19-year-old lefty playing at the local junior college.

Like most athletes in his situation, Clayton was willing to try anything. Which is great because, as you probably know, my training style is untraditional. But it works. His program consisted of two themes: tendons and pitching mechanics. I know, super broad. Let me explain.

TENDONS

On day one, I asked if Clayton could hang on a bar with one hand. I used this test to give me a general sense of the strength of his whole body, arm, and grip. (Grip strength is related to total muscle strength.) The stronger, more consistently healthy Apiros athletes can hang from one arm for fifteen seconds or more. He made it zero seconds. This told me two things:

-

To pitch well, Clayton needed to be able to transfer forces from his body to his arm. This simple test told me he couldn’t do that well.

-

For his arm to last, he needs the capacity and strength within the muscles of his forearm and hand. This test also told me those muscles and tendons needed lots of work.

If his arm muscles failed these strength tests, his tendons also needed work. Many of the muscles (and their respective tendons) that control his hand, wrist, and fingers attach at the elbow, right where he had pain.

Based on his hanging, I wanted to run another experiment: if we increased the strength of these muscles, they would increase the robustness of his tendons, his elbow would feel better, and he would hang longer.

This blog post isn’t the place for the details of our training, that’s reserved for my educational course and sessions with athletes, but I will explain my big-picture concepts.

Every baseball player that has walked into Apiros, except for Hunter, has had weak hands and fingers. Yet they rely on their finger-knees for their sport—especially pitchers! Pitchers experience 115 percent of their body weight in distraction forces on their shoulder when they throw. (Distraction forces are basically pulling-arm-out-of-socket kind of forces.) The force on their hand, I estimate, is much greater. Yet they can’t statically hang a mere 100 percent of their body weight from a bar? They can’t hang from the same fingertips they use to hurl the ball? Red fucking flags—and they’re waving within baseball players around the country.

I trained Clayton’s shoulders, elbows, wrists, and hands as if he was a rock climber. He approximated one arm pull ups, he trained the hell out of his hand and forearm muscles until he could easily hang from his fingertips, and of course he climbed too. Not only did we increase the capacity of his stuff-touchers, I changed how he used them when holding onto things. Human hands are incredibly complex and have better and worse ways to be used, better and worse ways for bones to be positioned. Not surprisingly, he and other baseball players have somewhat mutated hands because of their sport—fingers, palms, and knuckles get all wonky. I changed that too.

So, Clayton and I increased the capacity of his muscles and tendons in his arms, a quantitative change. We also improved the minute details of how his phalanges folded—a qualitative change. And yet, we didn’t fully resolve this puzzle because his elbow still bothered him. Less so than before, but the pain was still there. I knew I had to tweak more quantitative and qualitative traits within his arm.

Quantitative traits are measurable: how strong his muscles are, how long they can endure, how intensely and quickly they can contract, all of which relate to the capacity of his tendons. Those are simple to change but require hard work. He was tolerant to the current workload I prescribed, so I increased the intensities on his muscles and tendons, as well as the total volume of work. Basically, he worked his hands with heavier loads and did more reps and sets. That helped but didn’t eliminate his pain completely.

Qualitative traits are more elusive: where his bones are positioned, how he moves. I had a sneaking suspicion that we needed to improve his supination because his wrist didn’t turn as far as it should. Time for another experiment.

We hammered his supination every which way I could imagine. Here are some examples: If he was hanging, he’d “supinate” his entire body because his hand was fixed to the bar. If he did a pull down, he pronated and supinated his wrist during the motion. I had him hold onto a PVC pipe and crank out supination until he got normal range of motion back. We got really creative. During these sessions, he reported positive sensations right where his elbow bothered him. Dude, sweet. I love that subjective feedback, but I also wanted to put it to the test with pitching. Several weeks of pitching passed and our experiment succeeded and his elbow pain, finally, disappeared. But wait, there’s more!

Throughout our time together, he threw faster with less effort—82 to 88 mph. His control of the ball improved too, which he attributed to having so much more strength and awareness of his hand and fingers.

PITCHING MECHANICS

In addition to improving the muscles, tendons, and movement of Clayton’s arm, I had to change his pitching mechanics. All the above changes would be great, but they would be like improving a race car without addressing the fact that the driver still steers into walls. How the car is driven, how Clayton threw, needed to evolve.

There were four main problems: his wind-up, his front leg, his back leg, and his throwing arm. Sooo, nearly everything.

Wind-Up

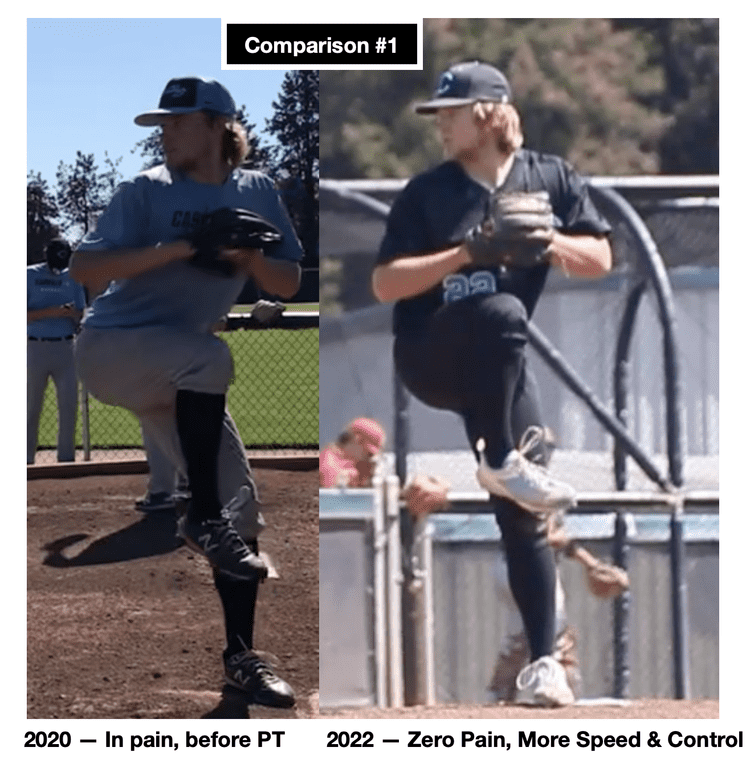

In 2020, Clayton’s rump eagerly reached toward home plate as if it were a toilet and he just ate bad Indian food. Do you see how far he tilted his torso, pushing his tuchus to home? Instead of loading his back leg in preparation to drive down the mound, he just leaned over it. Compare that to his vertical spine on the right, keeping his butt to himself. Why do I like this change? To put it simply: it puts his hip muscles in more advantageous positions to drive down the mound.

Secondly, notice that his left foot was not parallel with the rubber either. This was a problem because during his wind-up, he was trying to rotate his hips toward second base to create tension, to then “unwind” his hips down the mound, but he didn’t. Instead of turning within his hip joint, he just turned his foot. On the right, you see his foot parallel to the rubber because he turned his pelvis around his femur instead of spinning his foot in the dirt.

As you’ll learn, these two changes—his spinal tilt and hip joint rotation—were essential prerequisites to take some of the strain off his arm in later pitching phases. They also helped him pitch faster. Woo Hoo!

Front Leg

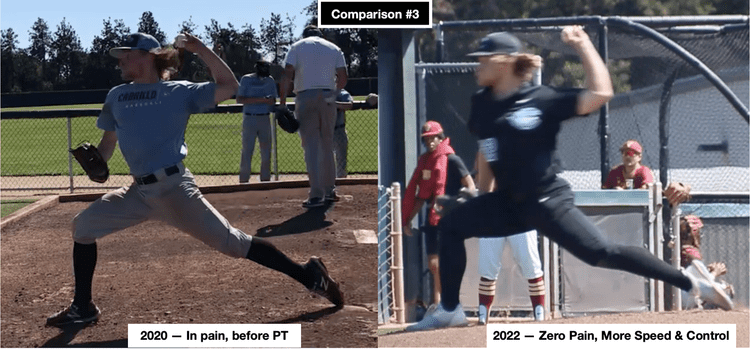

Clayton used to land on his toes, (see the left picture). Merely standing on your toes is unstable. Pitching onto them is even worse, especially if you want to throw with power and accuracy. Toe-pitching made his arm work harder, gave him less control, and arguably limited its speed. We changed that. See the right picture: he landed on his heel, kept it down too as his weight shifted forward. Finally, a leg to stand on. He needed a stable foundation if his arm was going to be fast and safe, otherwise his arm was doomed to overwork.

Back Leg

Notice that the Clayton of 2020 rotated his back leg before his front leg was on the ground. His toes on his back foot point down. Clayton of 2022 does not prematurely rotate his back leg. Good rotational sequencing—hips rotating after the front leg is down—is healthy and powerful pitching. Some people can get away with bad sequencing. But if they get hurt or are inaccurate, it’s one of the first things I’d change.

Throwing Arm

If you still look at comparison #2, notice where his left arm was once his front leg hit the ground. In the 2020 photo, his hand was already behind his head. Way too early. He cocked his arm before he had a leg to stand on. The better sequence is this: his front heel hits the ground, then his hips rotate, then his arm comes up. That’s what he does now.

Planned, Positive Side-Effects

In this third comparison, notice the angles of his elbow, where his hips point, and the fact that in 2020, his heel still hadn’t hit the ground. Here’s my rundown of those three elements:

-

Elbow: I didn’t coach him to change his elbow angle because I thought it was a bad byproduct of his setup. I prefer the ninety degree angle on the right. What led to its improvement was what I stated above: his front heel and the timing of his left leg and arm. The end result? Less strain on his elbow, faster pitching velocity, increased spin rate, and more control of the ball.

-

Hips: If you scroll up and compare photo #2 with #3, you’ll see that 2020 Clayton did not continue to rotate his hips from one image to the next. His hips didn’t rotate well because he had such an unstable front leg. Now they do. In 2022, there’s a drastic difference in pelvis position from #2 to #3.

-

Heel: Since I’ve already made my points about his heel, I’ll mention an observation: I see an odd paradox. In the weight room, coaches endlessly tell athletes to drive through their heels to engage their posterior chain…yet so many pitchers continue to pitch from their toes, arguably getting less from their powerful butt muscles that their coaches are always on about.

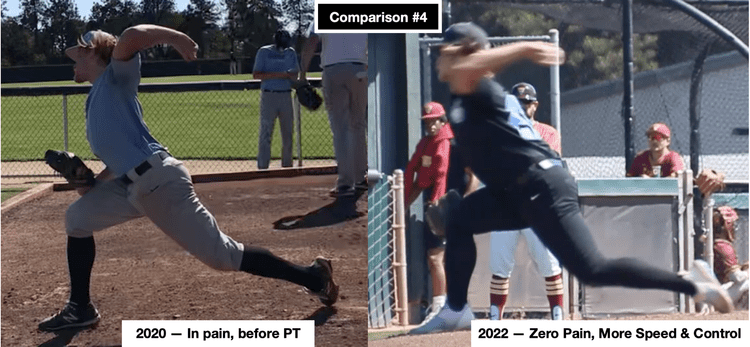

The last notable side-effects are shown in the fourth comparison: a more vertical spine, and way better layback of his pitching arm. The phase shown in this photo happens in nanoseconds. If he tried to control it while it was happening, well, he wouldn’t. It has to be a byproduct of what happened earlier. In the left photo, he struggled to generate necessary preceding power from his legs so he side bent his spine as a last ditch effort to throw gas. On the right, his legs did the work, his spine rotated, and his arm was allowed to whip. The left photo had more arm work, and I’d argue, more elbow strain. The right is a beautiful display of movement and pitching.

Clayton’s career went from dead-ending against his elbow to seeing how far he can take his pitching. As long as he stays healthy and has robust tendons, he can continue to increase his skill and improve his power. So we vigilantly protect his health.

He just finished his first pain-free season in years, and he finally feels confident in his arm again. Before working with me, Clayton’s fastball went 82 miles per hour. Now it goes 88 mph, and is likely to speed up. His accuracy and spin rate also improved, vital metrics if you’re going to make it as a pitcher. These pitching stats were byproducts of our program—just like a car’s speed and control are byproducts of good engineering. He’s able to throw faster with less effort, and that kind of efficiency is essential if any pitcher is going to have a long, successful career.

-

If you’re a baseball player like Clayton, reach out.

-

Are you a coach who wants to learn my methods? Take my course or buy my book.

-

If you want to see the videos of him pitching, here you go:

Citations

-

Laudner, Kevin G., Regan Wong, and Keith Meister. “The influence of lumbopelvic control on shoulder and elbow kinetics in elite baseball pitchers.” Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery 28, no. 2 (2019): 330-334.

-

Bohm, Sebastian, Falk Mersmann, and Adamantios Arampatzis. “Human tendon adaptation in response to mechanical loading: a systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise intervention studies on healthy adults.” Sports medicine-open 1, no. 1 (2015): 1-18.

-

Cronin, John, Trent Lawton, Nigel Harris, Andrew Kilding, and Daniel T. McMaster. “A brief review of handgrip strength and sport performance.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 31, no. 11 (2017): 3187-3217.

-

Wind, Anne E., Tim Takken, Paul JM Helders, and Raoul HH Engelbert. “Is grip strength a predictor for total muscle strength in healthy children, adolescents, and young adults?.” European journal of pediatrics 169, no. 3 (2010): 281-287.