I’m attempting something rather large in this particular piece, knowing full well that I’ll fall short. What I’d like to propose is a reconception of the phenomenon of depression. I make no claims that this is “right.” And it is not a complete picture of depression, which is an incredibly complex phenomenon. Rather I’m basing it on my personal experiences alongside a theoretical understanding of the processes involved.

I can only hope that this first approximation is coherent and can provide a foundation for continued investigation.

The Theory of Logical Types

Let me begin with a discussion of Bertrand Russell’s Theory of Logical Types, a model that I believe is of great importance for us if we’re to understand depression. It was developed in the book Principia Mathematica, and I was introduced to it through the work of Gregory Bateson and Paul Watzlawick (who was under Bateson’s theoretical supervision at the Mental Research Institute in Palo Alto, California).

The Theory of Logical Types was developed as a way to understand better the problems of paradox that occur in logic. It involves ideas along the lines of: a class (also known as a category or a set) of objects cannot be a member of itself, the map is not the territory, and a name is not the thing named. For example the word “cat” is not itself a feline. Therefore the word “cat” does not belong in the category of “cats.”

It may seem trivial, but it is crucial to understand this if we wish to think clearly.

We’ll later return to the idea that “learning about learning” is not of the same logical type as “learning.” Nor is feeling guilty about an action the same as feeling guilty about one’s guilt. The rules and ideas that apply to members of a group do not apply to the group itself. The group occupies a position “meta” to its members.

But I digress…

The important final part of the theory is that if the rules of logical typing are violated, then a paradox ensues, and — in the abstract world of logic — the series of propositions falls apart. It is reduced to nothing, as if it never happened.

However, the world of logic is very different from the world that we inhabit in one key aspect. The world of logic does not contain time. Within logical problems, all events occur with a sort of simultaneity, however, this isn’t the case for our problems. Nothing that we’ve ever experienced can completely go away because time is a necessary component of our lived experience.

Think of Groucho Marx’s joke: “I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as one of its members.” Logically this falls apart, but we can make sense of it nonetheless. Paradox in human affairs is quite funny or quite tragic, depending on the situation.

Depression, and The Depressive and Paranoid-Schizoid Positions

In light of what has been discussed concerning the Theory of Logical Types, I believe an understanding of what the psychoanalytic tradition calls “positions” will help us understand what’s taking place in depression. Depression has been said to be “a consequence of an individual’s not having been able to work through the depressive position” (1).

The depressive position is not to be confused with depression. The depressive position is considered a normal process in human development, a stage that follows what’s known as the paranoid-schizoid position. In human development we are said to move through these two stages early in life, and we may return to them if confronted later in life with a stimulus that exceeds our ability to cope.

The paranoid-schizoid position is characterized by an “all or nothing” quality. All experiences are perceived as absolute. The developing infant is claimed to feel something along the lines of “all that is good is me. All that is bad is not-me.” A schism is found between the good and the bad, and as Kipling writes “never the twain shall meet.” Hence the term “schizoid,” which refers to the schism. The term “paranoid” refers to the tendency to alienate oneself from the bad.

We may revert to this paranoid-schizoid position in times of duress. Consider the case of a car accident in which the other driver is felt to be totally responsible…and an irredeemable idiot…and obviously ugly…and probably has bad breath and a terrible sex life.

We are said to split these qualities from ourselves and project them onto the other.

While this position may be a perfectly natural part of our early development, we continue past it when we begin to recognize that the world isn’t so black and white. We find for example that we may actually have some downsides, and that the bad stuff “out there” isn’t entirely bad. This is understandably a very challenging psychological situation to reconcile.

Bad?

Moi?

How could this be?!

Hence, the depressive position, in which we feel a sense of guilt over the shortcomings of our character. Safe to say this guilt can leave us feeling a bit down, as if we’ve let ourselves down. Compared to the way we previously saw ourselves, this could entail a perception of being lesser than or beneath. I emphasize these because we’re about to take a necessary detour into the world of metaphorical representation.

How Do We Experience Depression and the Depressive Position?

First I begin with an assertion, namely that we inhabit three interrelated landscapes in our lives: the material, the symbolic, and the psychological. There is a “real world” with which we interact as a body. That’s the material landscape, the stuff I bump up against, touch, eat, etc. There is also an undeniable “psychic reality” that we experience in our own subjective way. I have a mental and emotional world that can only be experienced by me. And there is an intersubjective “symbolic reality,” through which it seems that we communicate our subjective psychological experience. I use words to express what’s going on “internally” for me, words that we have previously established are names for the thing, not the thing named. Hence symbolic.

As I mentioned above, the depressive position is associated with a feeling of guilt over behaviors, thoughts, and feelings which we perceive as “bad.” We recognize that we — previously “all good” — in fact contain some of “the bad.” And what are the words we use to describe the subjective experience of guilt? We’ve let ourselves down. We feel less than. We feel beneath. We feel as if we’ve dug a hole for ourselves.

These symbols are representative of a change in spatial orientation, specifically a change in elevation. Are we actually closer to sea level in the material world when we experience the depressive position? No. Actually, yes – somewhat. Consider the physical manifestations of this: slumped, hanging the head, the mopey sunkenness, the downcast gaze. Perhaps we are literally lower in space, but the symbolic representation of the words is the most important thing here. Through them one communicates a subjective psychological experience.

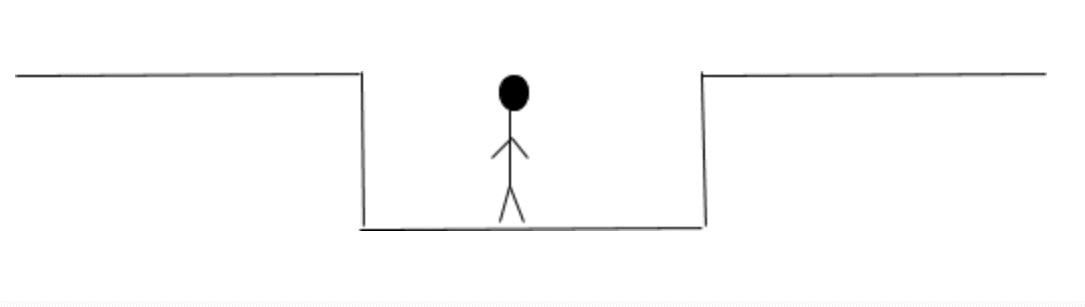

If I were to draw (another symbolic representation, through which a different sort of information is communicated) the experience of someone who’s feeling a bit down, it might look something like this:

Predictably this person will also have the experience that every time they try to move forward they are blocked or they hit a wall. Maybe they feel that they’re going nowhere or are going in circles. At a certain point, if they can’t figure out what to do, they may just sit there. All of these verbal representations, if applied to the metaphorical situation, will of course do nothing to get the individual out of the situation. They’re still in a hole of sorts.

Within the world of metaphorical therapy (best developed in my opinion by the recent work of Andrew T. Austin), the solution to this particular metaphorical situation is to grow up. This is taken literally within the metaphorical situation. The individual is asked to imagine stretching themselves, growing larger, taking up more space. As a result they grow up and out of the container in which they previously found themselves stuck.

They are of course then not guaranteed the sort of protection and invisibility offered by the container, but most people find growth and maturity far preferable to prolonged time in the hole.

It must be said that the cavalier advice to merely “get over it” won’t help much because getting over it is precisely what one cannot do while in the depressive position. Simply climbing out of the hole performs a kind of trick. It substitutes status (a change in elevation within the metaphor) for growth. Some people “get over it” by artificially boosting their sense of self-esteem through expensive shopping, posting on social media, and the like, all of which are status grabs.

The problem with substituting status for growth is that one is still susceptible to being trapped in the very same hole if they should ever fall back into it.

An Aside On Communication & Meaning

Before we continue onward to the relationship between the depressive position and depression, it is necessary to make a point regarding communication and meaning.

First, to quote Paul Watzlawick, “we cannot not behave.” Thus we cannot not communicate. Communication is always taking place because behavior is always taking place – even in the absence of speech and action. If we pull from the root of the word “communicate,” we may safely say that something is always being shared.

As laid out by Bateson (2) communication is meaningful in two ways:

-

It is meaningful in that it influences behavior of the recipient of communication (it is worth noting here that oneself can be the recipient of one’s own communication).

-

In the event that the communication does not influence behavior of the recipient, the ineffectiveness of the communication influences the behavior of both parties.

For example my communication in this piece hopefully influences the way you engage in the world, with you at the very least nodding along in agreement. Its failure to do so may lead both of us to change our behaviors, you scratching your head and wondering what the hell I’m talking about, and me banging my head against a wall trying to communicate more clearly.

Simply put, my failures communicate something just as much as my successes do.

Back to the hole…

Depression As An Error In Logical Typing

Let’s return to that individual in the depressive position who is feeling guilty about his behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. Note that his behaviors, thoughts, and feelings belong to a particular class of behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. If he attempts to change his behaviors, thoughts, and feelings, but chooses from within the same class of behaviors, thoughts, and feelings, he will in all likelihood remain in the same situation.

He will be making an error of logical typing, attempting to change behaviors, thoughts, and feelings when what is called for is a change of class of behaviors, thoughts, and feelings.

His failure will communicate something just as much as his success would have.

However, his failure to effect a change communicates a dangerous informational message, namely that he may be incapable of making the change which he so desperately wants.

If you recall, the paranoid-schizoid position is characterized by the absoluteness of experience.

In essence, the person occupying the depressive position may shift into a paranoid-schozoid position called depression as he begins to feel like, “I’m awful. I’ve always been awful. I’ll always be awful.” The absoluteness conveyed by the informational component of repeated failures to change goes above and beyond the existing guilt about behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. It becomes guilt about the context of behaviors, thoughts, and feelings.

Put differently, I posit that — while the depressive position is related to guilt about the behaviors, thoughts, and attitudes — depression is related to guilt about the class of behaviors, thoughts, and attitudes (and failure to change said class).

As such it is guilt of a different logical type than the guilt of the depressive position.

It is a “metaguilt.”

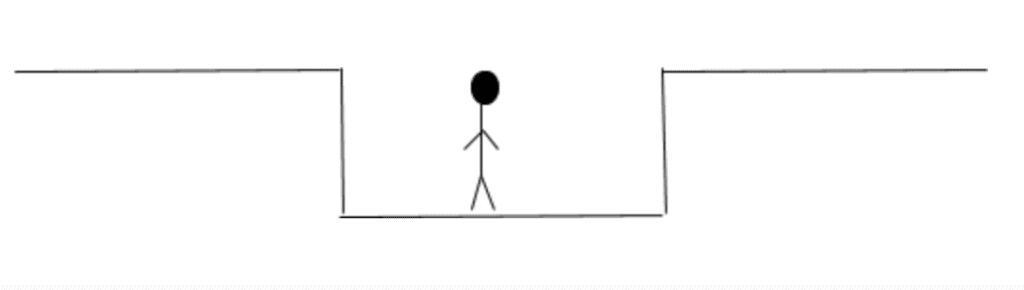

The hole of the depressive position becomes a pit in this case, perhaps stretching downward into an achingly infinite chasm of cataclysmic proportions, seemingly too deep and too vast to possibly grow out of (as I’ve felt at times in my own metaphorical representations).

The question of personal and clinical importance then is how does one possibly grow out of a pit that big? How does one cope with metaguilt in depression?

Reconciling The Metaguilt of Depression

As clunky as the term “metaguilt” may be, I believe it’s important in understanding how we may do the difficult work of reconciling depression.

We can infer — and validate through patient experiences — that the pharmacological approach, while vital and life-saving in some instances, is problematic if overly utilized. What does it do to the psychological reality, symbolically represented as a hole? It flattens the landscape. Indeed this is often the related experience of those living on antidepressants. The world is muted. Although lows aren’t so low, the highs aren’t so high. In the worst cases life becomes a miasma of undifferentiated middle-range experiences. Not bad. Not good.

Surely we are capable of more than merely flattening the world.

Surely with an understanding of the “meta” nature of depression we are able to deconstruct this perceptual frame of reference and instill a different one.

I turn again to Bateson (3) for advice in navigating the logical levels.

In his essay “The Logical Categories of Learning and Communication” Bateson discusses what he calls levels of learning:

-

Zero learning, characterized by a specificity or fixedness of response.

-

Learning I, characterized by a change in the specificity of response (chosen from the same category of behaviors).

-

Learning II, characterized by a change in the change of specificity of response, or a change in the category of behaviors from which I choose.

-

Learning III, characterized by a change of the change of L2, in which I may change the categories of behaviors more proficiently or change categories in new ways.

-

Learning IV, which practically speaking, doesn’t occur.

It is worth noting that in Bateson’s hierarchy religious conversion, Zen enlightenment, and effective psychotherapy are referred to as L3. L3, however, also contains psychosis, so it is important to tread lightly. Interestingly, the mere swapping of one L2 for another wouldn’t qualify as L3. Going from “only depressed” to “only elated” isn’t exactly a healthy change.

In discussing the achievement of L3 (which we’d know as a successful therapeutic intervention or the dissolution of metaguilt), Bateson identifies four strategies:

-

Achieving a confrontation with the premises of the patient, dismantling their worldview. I liken this to John Boyd’s idea of “destructive deduction,” in which we tear apart a frame of reference and are then able to make use of “creative induction” to build a new one.

-

Get the patient to act in ways that confront his own premises. That is to say that if I identify all of my actions as belonging to the class of those actions called “depressed,” then what happens when I act in such a way that my actions can no longer fit in the category of “depressed.” This I find a bit slippery because one could easily mistake this for the “fake it til you make it” phenomenon, which is utter garbage.

-

Demonstrate a contradiction in the patient’s premises, showing them for example that they don’t always act in such a way as to be called “depressed.” This provides the germ of discernment, from which they can develop an appreciation of the fact that their situation isn’t absolute (as it is seen to be in the paranoid-schizoid position).

-

Encourage the patient into some exaggerated experience of their situation. This I liken to the idea of enantiodromia, in which everything is said to contain its opposite if one ventures deep enough into it (symbolically represented by the yin yang). This strategy of course carries risk in that encouraging someone depressed to venture deeper into the pit risks them losing themselves within it.

In my personal experience — reinforced for me by experiences with clients as well — there is comfort in the physiological fact that if you can perceive it, you are not it. That is to say that the act of perception implies a distance from the thing perceived. This perhaps relates to the first strategy mentioned above in dismantling a person’s identification with the depression.

This is reinforced by the optimistic idea that if you can perceive the situation, you are capable of engaging it. If the situation truly were too great to bear, the assumption is that you wouldn’t perceive it; you’d be catatonic or delusional to avoid perception. This again relates to the first strategy in dismantling the premises of the informational situation created by repeated failures to change: “I can’t do anything about this. I’ve never been able to do anything about this. I’ll never be able to do anything about this.”

I say the following in the spirit of the title of a book by James Hillman, We’ve Had 100 Years of Psychotherapy, and the World’s Getting Worse.

I think what’s needed in the reconciliation of the metaguilt of depression is a reconceptualization of the self.

A personal anecdote may be illustrative…

I have long thought of my depressive moods as being pit-like in nature: I get in over my head, I like to go deep, I’m down, I dig myself holes, and so on. However, a recent experience left me with a very different sense.

In its symbolic representation I found that I had fallen into a pit beneath the hole, having dropped farther down than I had ever experienced before. I found myself with my back against the wall of a cliff, very, very far down. So far down that if I looked way up I could see the faintest pinprick of light overhead. That pinprick of light was coming from the hole that I had known previously. Thus I was in a very different pit, far deeper, a chasm of titanic proportions. Within the metaphor there was nothing to the left. The cliff simply ended. I felt as if I had nothing left. To the right was only darkness, too dark to see. I couldn’t see what was right for me. My back was against the wall of course, and in front of me was a swirling mist, a fog, a crackling thunderstorm, through which I could — in brief flashes of lightning — make out the awful form of some mad, bleating, hundred-headed beast. All I had to look forward to was…well, Hell.

Let me take a moment to make an important point.

Previously I had felt guilty about having dug a hole for myself.

And as I found myself in this new nightmare scenario, the thought came to me with blinding clarity: this pit is too old and too deep for me to have dug by myself. I couldn’t have dug this in a hundred lifetimes.

I can’t explain it rationally, but I had an unshakeable sense that this was a pit my father and grandfather and many generations before them had helped dig.

In that moment I came into a very different relationship with the pit. No longer was it solely my fault, so to speak. No longer was I guilty of digging my way into Hell. With that realization I began to grow…

It struck me that I had inherited a wound that stretched far beyond the narrow, Western conception of self-as-merely-oneself. I realized that if I had inherited the wound, perhaps I also inherited the wisdom. I had an uncanny experience that I somehow stretched beyond my flesh, backwards through time, as my ancestors’ unavowed wish. I stretched outward through space, the embodiment of an idea given form through borrowed stardust. I felt the world within me as much as I felt that I was within the world. I inhabited a very different psychic reality, in which I was big enough to face the beast in the mist and big enough to not be trapped in the pit.

Perhaps this exemplifies that fourth strategy, enantiodromia.

What I am trying to say is that a reconciliation of the metaguilt of depression seems to beg for a reconceptualization of the self. This is not a growing up merely in terms of maturity, rather — as the deep ecologists say — a broadening and deepening of the self.

This, however, is not something we gain through intellectualization, despite the amount of it I’ve done in writing this piece. This is something we gain only through experience. This experience seems to require a participation within our material, our symbolic, and our psychological worlds.

It is an experiential shift in our very mode of being-in-the-world.

What I hope to have done with this piece is provide a map of sorts, knowing full well that the map is nothing more than a concept. But perhaps with a map in hand we may navigate more effectively.

-

Roth, Priscilla. “The depressive position.” Chapter 3. Introducing Psychoanalysis. Routledge Press, 2005.

-

Bateson, Gregory. “Problems in Cetacean and Other Mammalian Communication.” P. 364-378. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. The University of Chicago Press, 1972.

-

Bateson, Gregory. “The Logical Categories of Learning and Commnication.” P. 279-308. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. The University of Chicago Press, 1972.