THIS ARTICLE IS ONLY ABOUT TWO THINGS, REALLY. IT’S ABOUT HOW THE HUMAN ORGANISM IS DESIGNED AND HOW IT LEARNS.

Since sports require skills, improving them is perhaps the one thing coaches are responsible for, by the current definition of the role. However, most coaches know almost nothing about the topic. A paralyzing perplexity that has many causes. (The causes are addressed in my book.) There’s a significant and overlooked difference between skill and technique. Technique is shaping and teaching one tool of many. Skill is knowing when to use the tool. Often times, techniques are taught in excess without ever being given the opportunity to use them in the right context. Secondly, most techniques taught are wasting time. They are often unnecessary, taught poorly, or perpetuated myths. When technique is well understood, it can be a great aid in the advancement of skill. However, most coaches need to take a deep and hard look at what they are teaching.

Coaches who talk about technique must also understand some basic principles of human movement. Asking for sport techniques without understanding simple foundations of what is possible with the tool at hand — the human body — is a bit like trying to optimize and race an F1 car without any understanding of how the engine puts power through the wheels to the ground.

A two-part perspective shift is desperately needed within the realm of athletics. Currently, practitioners and coaches first look to adapt the athlete for the sport — like trying to get a driver to drive a car fast while the car is barely staying together. It doesn’t matter how fast you drive if you can’t finish the race. A philosophy with more sense is optimizing the human movement system first, and how it performs in sport second. Meaning, the driver is safe, the car endures, and the driver and car have a safe relationship between skill and engine power. That way, the car is always available to improve driving skills and have fun. Mind you, there are no replacement parts for this biological vehicle either, and big injuries leave dents that last and last. Bottom line: optimize the human first and the athlete within second.

The second perspective to adopt is the idea that the body and nature signal what is best, and we simply need to listen to what they say. When a child is no longer having fun in the umpteenth game during the umpteenth tournament, it is not laziness or a lack of discipline, it is his biology trying to get him to rest by removing interest from the damaging activity. Promoting natural movement environments for humans will yield exponential results. What are natural movement environments? Variations that are fun, simple, and novel are what our biology loves and requires. So give it diverse and novel environments and games, and exploration fueled by curiosity instead of restricted by anxiety. These two perspectives are all we need to progress in this article and in athletics.

The basic fundamentals of human movement are: squatting, hip hinging, sprinting, running, jumping, throwing, climbing, hanging, and swinging. It’s most odd that many volleyball players can hit a volleyball with exquisite power and accuracy, but when they are asked to throw a ball, you wonder if this is his or her first time… Throwing well is not a prerequisite to hitting a volleyball but it certainly helps. These fundamentals are best served when they are the products of games and play. Run fast, slow, long, short, and sometimes random directions. Chase and be chased. Jump high and far and in varied ways. Climb walls, trees, parents, friends, whatever. Swing smilingly from branches, bars, and overhung walls. Hang daily from something. Throw and catch. If all these movements are seen consistently throughout life, and as a product of games and play, there won’t be a whole lot of nitty-gritty mechanics issues to clean up. Optimize the human first and the athlete will blossom as a result.

It should be noted that these responsibilities of movement and skills are not exclusive to coaches. They can just as easily be the athlete’s — a level of autonomy and ownership that is most excellent if you ask me.

ORGANISM DESIGN

The shoulders and arms that humans possess are the offspring of primate shoulders. They share many of the same traits. Now, imagine if you had a pet monkey, yet removed any and all things for it to climb on, hang from, or swing to and fro? Not only would you have an angsty monkey, but you would also be removing the very things it needs to be a monkey!

A rich overhead environment and all associated behaviors are what his shoulder and body expect and require to be robustly functional. This monkey deprived of monkey-ing around results in an increased risk of injury when the monkey decides to suddenly grab a banana flung through the air, play volleyball, or throw heaps of poo.

Consider the environment of the modern athlete. We see the exact same deprived scenario that our poor hypothetical monkey has suffered. Our shoulders are designed for arboreal environments yet are without any of the vertical challenges that they need. Furthermore, the rotator cuff itself did not show up in mammals until overhead behavior was necessitated by the environments in which they lived. We are fish out of water, of sorts. More accurately stated, we are monkeys without trees.

Realize that overhead sports, volleyball especially, are asking athletes to perform overhead without the primary and fundamental environments that ensure shoulder integrity! Volleyball organizations should have climbing, hanging, and swinging environments for their athletes to utilize and benefit from. If you optimize the human first, then adapt it for a sport later, you will have a body that is prepared to perform at a high level, year after year. To ask for innumerable repetitions overhead, without prerequisite and concurrent climbing, hanging, and swinging activities is to drastically increase the risk of injury while steering towards perilous imbalances.

Any sport played enough will start teetering movement homeostasis towards dangerous imbalances. When sport is in excess, as it currently is today, it should be treated like a poison. Tournaments are overdoses and year-round structured practices are chronic use; sobriety is needed from time to time. There are two questions that everyone in sports is overlooking yet should be asking, “How do I mitigate the damaging effects of my sport?” and “How do I return to normal, balanced, movement, when my sports career inevitably ends?”

ORGANISM & ARM SWING

If you rid yourself of romanticized notions about how special the volleyball arm swing is, you can see that it is not much different than actions in baseball, tennis, badminton, or even soccer. All are various rotational patterns of the spine to move limbs to propel objects. Sometimes, the body dances amazingly to conjure unorthodox ways to score points, and we want to allow for those opportunities.

You or your athletes may end up with the most biomechanically sound arm swing science could ever ask for; however, if the tissues in the body are not tolerant to countless attacks, the risk of injury is still high. I wish this issue was black and white, but it is incalculable shades of grey. All we can do is lower probabilities of injury and increase probabilities of performance.

The primary analogy that is offered in my book is that movement is a cost from one’s Movement Bank account. These costs can return dividends, if cared for and smartly invested. One can also have high or low interest rates on these expenditures and loans, and bankruptcy can happen with irresponsible spending. I will utilize some Movement Banking language going forward to help get messages from me to you.

Due to the sheer number of serves and attacks in volleyball, we need to ensure that the cost of each attack is low and has a small interest rate. This is why we value a safe and sound “technique.” Astute observers notice that rotational athletes who endure and succeed have commonalities in their technique — as the hips rotate forward, the hand stays back.

What I want to see and coach for is just a few things. The elbow is brought back around shoulder height, the palm faces the ground before the hips start turning forward, and the arm stays relaxed throughout the entirety of the swing. How it gets to this loaded position is of the utmost importance. The rib cage ought to be the vehicle that carries the arm as a passenger to this loaded position. For someone who has a healthy overhead environment outside of volleyball, and unobtrusive coaches, this may be automatic. For the majority who do not, it will need coaching and a change in environment. Many will lack the intrinsic stability, mobility, and awareness to attain this movement easily. It will, and should, take time. A quick change will appease egos of parents, coaches, and athletes, but it is dangerous because an individual’s tissues are accustomed to high loads of a different flavor of stress. Quick changes are chancy. Biology is patient with change.

For those who have malnourished movement environments, it will be increasingly hard to feel what they are doing. Therefore, it will be hard for them to own their movements. They are driving the car but have little idea how to control it or where it is in space. Movements and sensation of movement are highly correlated. Some will need to feel the movement in simple, intrinsic, and isolated conditions before they can progress to something chaotic and externally focused.

I have seen a plethora of promulgated techniques that preach that a high elbow, or palm facing backwards, or something else entirely, is “natural.” They are lost and claiming to be found. However, I appreciate that they are sniffing in the right direction and well-intentioned. When they are asked to provide evidence for its “natural-ness” is usually when I hear a symphony of crickets or poorly made rationalizations.

What is natural has two sides: what is natural for humans and what is natural for an individual at given moments in time. If a coach sees an odd, or unexplained technique, it did not materialize out of the ether. It occurs because the athlete’s brain is choosing it as the most stable position for their body, at this phase in their life, in order to accomplish the task(s). So the next question to ask is, what caused such an odd deviation from normal movement?

Our brains will sacrifice biomechanical integrity in order to accomplish outcomes, which is quite similar to how many people live miserable lives yet accomplish a lot. Deviations from the ubiquitous natural usually occur because of concurrent environmental maladies. Long term, we want to see humans moving as humans are designed. Our design is the offspring of our environments, which must be cared for and created with care.

Much of the research talks about being overhead as an extremely stressful position. I would say it is potentially high risk rather than extremely stressful. This position presents a risk because there is less contact surface area with the arm and the socket, thus relying on muscle and connective tissue for integrity. These tissues, across all westernized civilizations, are ill-equipped to handle repetitive overhead movements. The issue is, the cultures that come with modern civilization have omitted overhead environments. Overhead athletes would be in significantly lower risk categories if they frequently climbed, hung, and swung from things on walls and above.

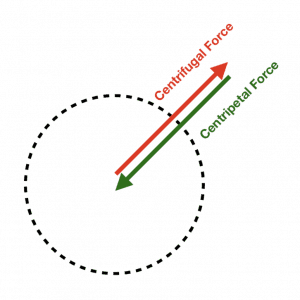

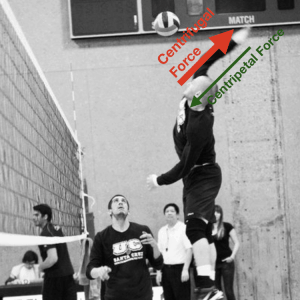

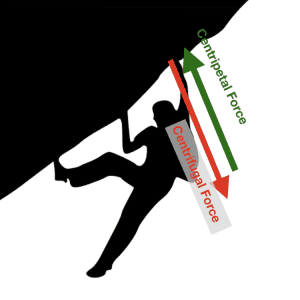

An overly simplified explanation of why those environments are useful is as follows: the arm swing projects the arm out of the socket. Climbing and swinging pulls it into the socket, relatively. The arm swing is mostly centrifugal force — a projective force away from the center. Climbing and swinging can be mostly centripetal forces — pulling towards center. This is because in one, the hand moves freely, and in the others, the hand is fixed. Hanging, having the arm fixed and the body free to move, will help prepare the body for climbing and swinging activities. If these activities are new to you, please proceed slowly, cautiously, and with a great deal of common sense.

When opposing forces are greatly unequal is typically when injury happens. We want balanced pushing and pulling forces during the arm swing. In this case, a rotator cuff tear could also be defined as projective forces beating receptive forces into submission (centrifugal forces being in great excess to centripetal forces).

In the images below, please note how the arrows of force have flip-flopped.

You now see that in the attack, the arm moves away from the fixed center of the body. In climbing, hanging, and swinging, the hand is fixed and the center (body) moves towards the hand. This philosophy can be viewed as a simple and common sense approach, balancing projective and receptive activities. Yin and yang.

You see, this isn’t a technique problem, it is an environmental and behavioral one. What I’m really proposing is an overhaul of environments. Second to that is the arm swing technique. The arm technique I advocate simply lowers risk by starting the arm swing in a more balanced position, and it produces faster ball speed as researched thus far.

To repeat myself, the starting position we want is simple: before the hips rotate forward, the elbow is at the same height as the shoulders and palm faces the ground. From a different plane of view, the elbow should not be behind the shoulder but rather in line, or in front of, as if hugging a very wide bear. Or imagine standing in a door frame and reaching both elbows towards the sides.

How the elbow gets there, I repeat, is via the rib cage. The chest rotates “open,” bringing the arm as a passive passenger. From then on, it is a roller coaster of a ride for the arm. There is no more coaching or cueing of the arm. We want to avoid yanking the elbow back to open the chest. If we want to unload rotation from the spine, we need to load it first.

How the arm goes forward to contact the ball is via the rotation of the hips. The hips are the front engine of the roller coaster, pulling the arm along in the back for a whippy ride.

*This is an abridged version of the article. The full post in its entirety can be found here.