A community class titled, “Self-Care for the Nervous System” made it’s way into my facebook feed and given the reasonable price ($15-$35, sliding scale) I decided to check it out. I knew very little about Rolfing going in, and I didn’t bother to research it should it create an expectation. I had heard the use of the term many times and knew it had something to do with manipulating gravity. The course was scheduled for 90-minutes, and was being led by Karin Edwards, a 15-year practioner and black belt in Aikido.

A post-course review of her website revealed some excellent conceptual frameworks:

The Role of Gravity

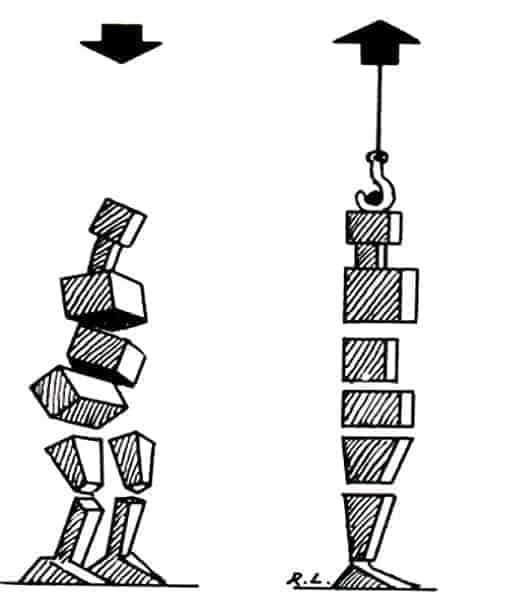

“Dr. Rolf recognized that gravity has a profound role in shaping the body. We have to balance our bodies, somehow, against the pull of gravity. From birth to death, gravity is always working on us. Consequently, deviations in the muscle-bone-fascia system are never merely local. Gravity’s influence requires adaptions throughout the body. If the natural balance of the body is disturbed, it doesn’t follow the best geometry of the skeleton, causing the whole body to gradually change form to adapt to the deviation.

For example, after an ankle sprain, limping to avoid pain can cause more trouble than the injury itself, especially if the limp becomes part of the person’s everyday gait. Since the body must work against the tug of gravity, the entire muscle and fascial system gradually shifts to compensate for the change. Movement through the pelvis is influenced, as are the patterns of breathing and the position of the head. Because muscles alone cannot carry the additional tension, the fasciae shorten to support the new movement, and, in time, the shape and function of the whole body alters with them.

The human body is like a house. It’s structured so that each part has its proper place, and each piece interlocks to balance the load of the others. As in the well-built house whose every post and beam is in place, the body that can move well will tend to continue to function efficiently. Because gravity pulls down on everything, out-of-place body parts are like beams unsupported by a post, and are pulled into painfully unnatural positions.”

Body Geometry

“Dr. Rolf’s view of posture led to still another major discovery. It might be called the theory of body geometry.

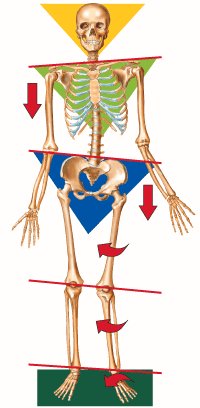

When an elbow, knee or any other joint is properly balanced, the individual experiences an internal sense of rightness. The body senses that it is aligned along the true planes of movement. The hinges of the legs (hips, knees, ankles, even toes) all work within a single plane. The paths of the legs have parallel courses. The head and spine feel a clear sense of “up.” The elbows move naturally through their angle in a smooth course. Compared with this new organization, the previous functioning of the body appears random, even chaotic. In contrast, the new geometry, this new orientation in space, feels much more secure.

This is often compared to hanging from a string emerging from the top of your head, in a perfectly vertical position, and then getting put back down on the ground but keeping that feeling of lightness and length. Putting one piece back into place is usually not enough. Everything should be right before a house can stand or a body can work smoothly.

Naturally, each person has his or her own version of this ideal geometry, which depends on height, length of limbs, and other similar factors. But Rolfers consider five basic points when planning individual goals for a client. In order for the human body to function properly and maintain an upright position, these five landmarks must be in alignment: the ear, the shoulder, the hip, the knee and the ankle. The head, neck and shoulders tell the story of the structure below them. The body should glide along, rather than look as if it has to do extremely hard work with every step. The head and neck must be centered over the middle of the body, and the spine that supports the structure must be at the back of the pelvic section. The spine must then curve in conjunction with the natural back curvature until it enters the base of the skull in a central direction. Any damage or constant pressure will disturb the balance of the upper torso.”

Holding Patterns

“One of the major distinctions made by Rolfers is the difference between holding and supporting. As children, most of us are told to “sit up straight.” The well-meaning family members who typically make this command are trying to teach us good posture, and by good posture they generally mean some variation of “chest out and shoulders back!” Try this posture right now as you read. Notice that when your shoulders are pulled back: they cannot be supported by the rib cage, that, instead, your trunk is lifted up off the pelvis and held in an uncomfortable imitation of good posture.

While sitting, most of us droop forward and let our bodies hang off our spines in various forms of collapse. When we do remember to “sit up straight,” we often reverse everything and hold our chests up and keep the shoulders high and aloft. Some people even become locked in this position. Although they look good to the untrained eye, most trained observers agree that the body structure is not supported from below in this posture; it is uncomfortably held from above. In either case, with the held posture or the collapsed one, energy is being expended. With proper structural support and balance, the body is more efficient, whether it is in motion or at rest in a static posture such as standing.”

What We Did

Parachute arms. Let arms float up (laterally) with the inhale, let your breath be small and easeful, arms only float as high as the breath allows.

Purpose: slow thoughtful movement activates parasympathetic nervous system. This is a vinyasa – pairing movement with breath.

1. Rest quietly for several minutes.

2. Begin to awaken yourself by brushing your fingertips along your face and neck.

3. Let your eyes softly gaze and explore the room, allowing your head and then your body to follow. Let your curiosity about the room around you lead you to come up.

4. Find a totally “inefficient” way to come up to a seated position on the floor.

Chanting. Om.

Purpose: Connecting to the group for social engagement, creating closure on one type of mental space and transitioning into conversation; activating vocal nerves which are connected to social engagement functions in face and neck.

**This list and its descriptions was graciously emailed out to the group the evening of the class. This generous act allowed us to participate more fully and for this experience to be easily transcribed here. The pieces that most resonated with me were the ones in which video have been recreated for. **